A new ESRC Global Poverty & Inequality Dynamics Research Network working paper takes a long-run view on the development of wages and living standards in Mexico. Its authors, Ingrid Bleynat, Amílcar Challú and Paul Segal, trace a worrying trend.

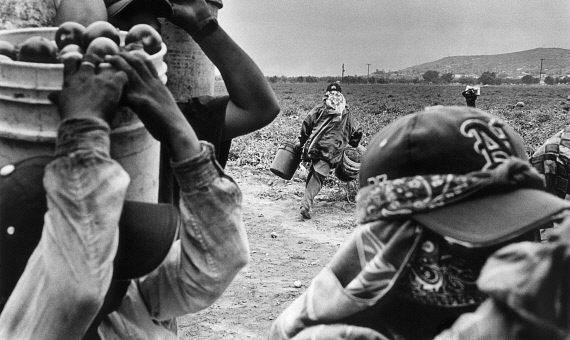

Nearly two centuries after independence and more than a century after the first major capitalist boom, not only has inequality soared to record levels in Mexico – the majority of Mexican workers have, in fact, barely escaped subsistence wage levels. What are the reasons for this stagnation? W. Arthur Lewis’ dual-economy model might hold an answer.

Bleynat, Challú and Segal use the ratio of per worker GDP to wages as a measure of inequality. They find that economic inequality in Mexico rose at the end of each of the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries. In present times, although output per worker has risen more than eight-fold since the nineteenth century, low-skilled wages have not even doubled since that time, adjusting for inflation. Such disappointing wage growth stands in contrast to developed countries where, despite rises in inequality, blue-collar workers have become dramatically richer over time.

How could Mexican employers get away with such a meagre pay rise over time? Bleynat, Challú and Segal argue that rapid population growth has kept adding people to a “reserve army of subsistence labour”, envisioned not only by Karl Marx but also an important factor in W. Arthur Lewis’ dual-economy model. The pattern of wage stagnation was broken only in the mid-twentieth century by institutional and political changes that underpinned state-supported industrialization, but reverted to its previous form in the 1980s.

Bleynat, Challú and Segal find much support for the Lewis model in explaining the lack of wage growth in Mexico.

Looking into the future, the authors are cautiously optimistic: lower population growth could lead to a withdrawal of the rural reserve army and thus bring Mexico to the ‘Lewis turning point’ at which low-skilled wages start growing – unless labour-saving technologies get in the way.

Recommended reading:

| WP 4 | Ingrid Bleynat, Amílcar Challú, and Paul Segal | Inequality, Living Standards and Growth: Two Centuries of Economic Development in Mexico | 29/09/2017 |